'ANYWARE' (Don't Leave Home Without It)

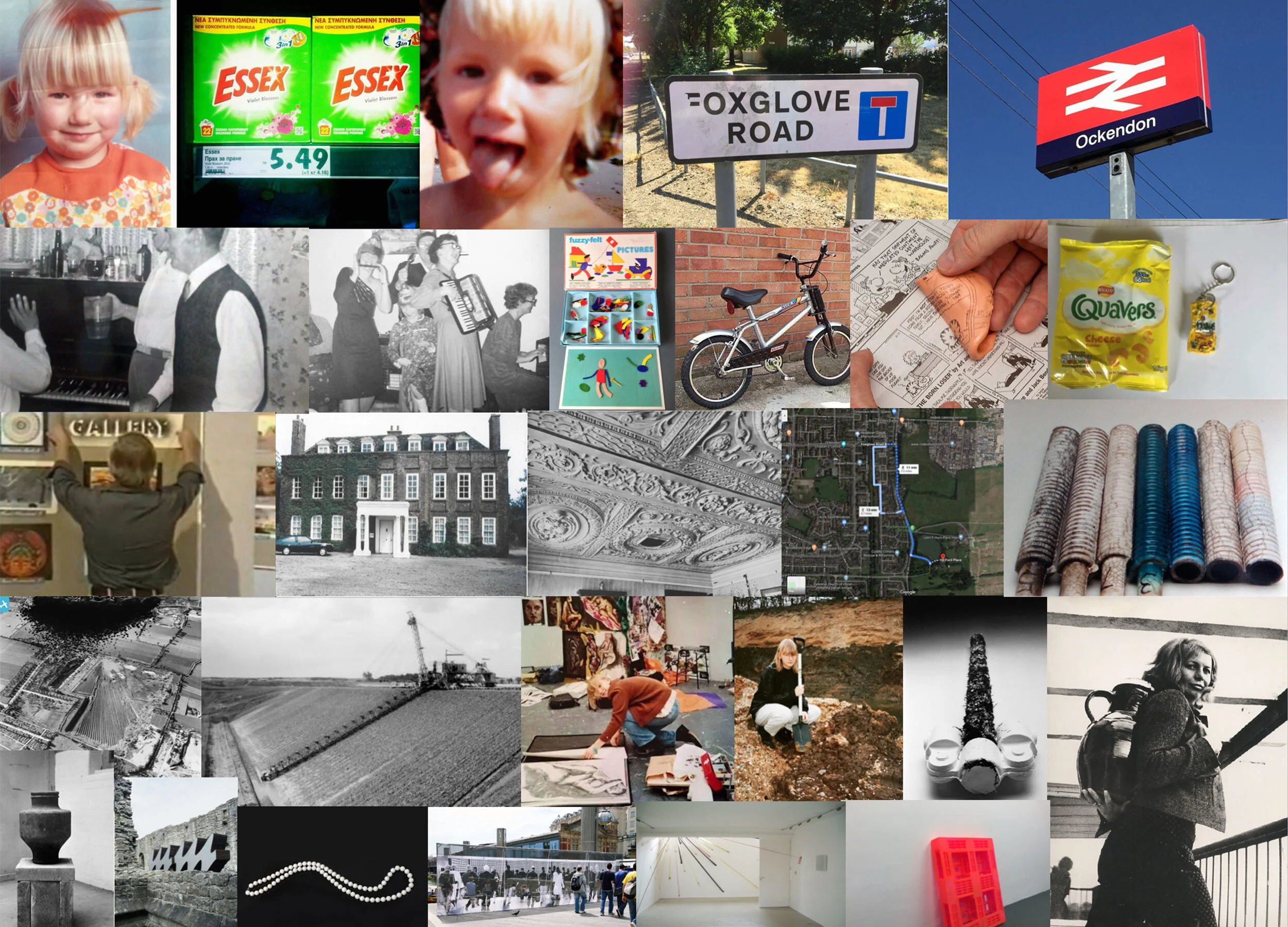

The image pictured above is from a presentation I gave in February 2020 at Art Bar (a series of monthly talks held at Renato's in Bristol). I was questioning my art practice around this time: whether to continue or to stop. My life interests and 'hobbies' were broadening, and I took the opportunity to reflect on my influences and experiences and began to notice connections between art and life. In my practice I was challenging territory with the materials I was using, and the spaces they occupied: large scale banner projects in public spaces explored fake history and perception; a pom-pom pulled the domestic into the public realm; oversized jewellery made connections to emotions associated with objects. I also enjoyed playing around with scale, creating installations and exploring the many facets of placemaking.

In my research for the talk, I learned more about the history of where I grew up in Essex - about a steady migration of Londoners building new lives in the countryside - a 'place of dreams'. I realised that imagination and practicality is Essex DNA. I also didn't appreciate until recently just how much of influence growing up next to industrial clay pits had been on me and my subsequent love of clay.

A core part of my work when making sculpture and installations is the material selection and research into new composites and methods. I make a conscious effort to learn something new, however incremental, and I particularly enjoy the juxtaposition of natural and synthetic materials. Separate to my practice, I also make clothes, preserve food and brew beer. I see a connection between all these processes through the quiet celebration of the every-day and the unheroic.

My first experience of throwing a pot was on my BA Ceramics degree when I made some lidded pots (above: Thrown Lidded Pot, 1993). I appreciated and enjoyed pottery, but I didn't connect with it as I did with ceramic sculpture. It was only when I saw Nadežda Plíšková's work 25 years later, and I had the opportunity to use a wheel again that my relationship with pottery shifted.

More recently, I wanted to improve my throwing and began by making tall cylinders that hinted towards design and craft. I then made Meoto Yunomi, Japanese inspired stoneware' couple cups' for a wedding present. I made more Yunomi during the Covid-19 quarantine. The clay helped me to feel grounded, and I decided to sell them along with some colourful earthenware pots. As well as furthering my learning, the proceeds have enabled me to purchase a brand new Shimpo wheel.

The Jugpacks I made, together with this blog, are to advance my research towards an extended essay: 'A Jug To Put On My Back: A critical exploration of clay, inspired by the work of Czech artist Nadežda Plíšková (1934 – 1999)'. This blog is the beginning of a process that I hope will expand my understanding of ceramics and what it means to me to be a 'potter'. I don't know if I have to do something specific to be called one, or if it is an affectionate name that ceramicists use to refer to each other by? For now, I am enjoying this new way that my work is connecting with people.

The following five blog posts explore topics I feel are pertinent to Jugpack:

Pottery: Making (and Faking) Tradition

Found Objects in Art and Ceramics

Strap It On, Ready To Go: Hi-performance Material

Perception, Function and Parlance

Permissions and Influences

Pottery: Making (and Faking) Tradition

My influences and interests are broad but often centre on the notion of function and the everyday.

Whether its distribution pallets, a broken necklace, or ornaments that haven't been moved around in a while, I find myself drawn to familiar objects that often go unnoticed or forgotten. A question I'm considering concerning ceramics and my art practice is: How can I bring more visibility to my pottery, to help it feel relevant to today, and to create new awareness and meanings around it?

I approach making sculpture with an initial question, 'how can I make this?' as opposed to 'how should I make it?' I also applied this thought process when making Jugpack. That's not to say that I don't intend to practise and refine my pottery craft. Still, I always analyse the necessary skills required for each new making scenario, and sometimes this will be different from a traditional approach. I also apply a problem-finding tactic that identifies a problem before it has happened; I find this to be a more positive approach. By bridging different styles and techniques across sculpture and ceramics, I combine a range of skills and materials-knowledge gained through my training as a ceramicist and in my years as an art fabricator.

In making Jugpack, I practised the technique of throwing on a wheel and gained an understanding of what it felt like to make and wear a ceramic jug on my back.

This traditional process of throwing proved challenging because of the massive lump of clay required; this then led me to draw on the skills and methods I apply when making sculpture. I forgot tradition and instead engineered this piece to make it appear traditional-looking.

To make Jugpack I scaled-up a photograph on a photocopier of the jug by Nadežda Plíšková to fit my back, then sectioned the image into three equal parts and estimated the amount of clay needed. I measured the diameter of the top and bottom of each section and made sure that the parts to be joined would be the same diameter with even wall thickness.

The jug sections were reconstructed on the wheel and then re-thrown to complete the pot. I made a wooden cut-out template that fitted around the form to enable me to cut a straight edge when cutting a third of the pot away, creating the flat back. This process reminded me of the 'You asked for half a cup of tea' cup that my Aunt and Uncle had in their bungalow in Billericay, Essex, which also had a flat edge. That cup taught me about volume and humour. I like to think of that half cup as a rebellious semi-functional ornament. I carry the spirit of it (on my back) through my trad-mod Jugpack.

Found Objects in Art and Ceramics

One of the reasons I incorporate found objects into my art practice, and its attraction as an artistic ploy, is that I often find the items themselves in obscure places. By using them in this way, their original context is lost, almost as abruptly as when they were discarded. This contrasting interaction between object and environment allows me to re-find and re-define the objects.

Duchamp is the go-to artist when thinking of found objects in art. He used the object as it was, sometimes combining it with another object or text. I often start with a found object, but I transform it either through scale (Pearl Necklace), casting (ECart), reproduction (The Day Before Today) or cultural appreciation (Jugpack).

I have been interested in found objects since my Ceramics degree in the early 1990s, when the title of my dissertation was Found Objects in Art & Ceramics. I was interested in exploring why I was drawn to ceramic sculpture and Fine Art. Looking back over the paper, I notice that, due to the availability of information at that time, most of my research was done on American artists. I researched the channels that ceramics passed through via the American 'Funk Art' movement from the early 1950s to late 1970s, to the 'Super Object' movement, and the attitudes of artists and critics about this new direction with clay.

Conceptual ceramics reached a high point in the 1970s in America when artists began to get involved in realism. Marilyn Levine (b.1935 Alberta – 2005) made realistic-looking leather boots and satchels, replete with scratches and signs of wear and tear, all made out of clay. A clay object made to look like a found object.

As a student, reading journals and finding out about the extensive range of ceramics in fine art that was being produced in America was inspiring to me. At that time, I didn't relate to domestic pottery and functional ceramics; it didn't mean anything to me. Until now, that is. Encountering the work of more British and European artists, especially female multi-disciplinary artists who use clay, has been hugely influential in my recent re-interest in clay.

Inspired by these artists, my interest in using found objects with ceramics continued after my dissertation, with Slipcast 1993. I created a plaster mould of a scaffold tube and used a slip-cast method to make the tube clamps so that this piece had moveable ceramic parts.

Found objects continued to have a decisive role as my art practice developed, and I am interested in reconnecting them with my journey in ceramics, albeit found, foraged or online.

Strap It On, Ready To Go: Hi-performance material

The neon yellow straps that I used for my jugpacks were an aesthetic decision I made after trying the traditional natural weave strap similar to what would have been used in the piece by Nadežda Plíšková. I found the natural weave to be 'old-fashioned' and difficult to relate to after fitting. It was also interesting to consider how much times have changed in 60 years since Nadežda Plíšková's piece was made: the difference in materials available for the strap then, and the high-performance materials available now.

I enjoy the juxtaposition of 'traditional' brown-coloured ceramics and the hi-performance neon straps. The straps suggest action and robustness, and while the jugs look robust, they are inherently more fragile by nature of their material. There is increased visibility through the contrast of materials and the suggestion that it can be worn on someone's back for an activity. The dayglow straps suggest functional wear, practical accessory and gadgetry signalling it as a familiar and usable contemporary object (albeit a curious one).

My research continues as I revisit the pots that I am most familiar and fond of, and as I consider combining them with other materials to create new pieces. When I think of brown ceramic ware and its uses, I consider the subtle handle designs which give a visual clue as to how that particular bowl or pot is intended to be used. For example, a vintage brown stoneware French onion soup bowl has tab handles for lifting, and a lip that invites a fitted lid. The lid may be lost or could the lip be intended for a different use? What potential is signified in each element of the design and what meanings can be suggested by the materials used?

Perception, Function and Parlance

What am I carrying and where?

One of the Jugpacks has a single pot handle with two back straps which suggests versatility and usefulness. The other has a spout. The concept of versatility is defined as the ability to serve many uses. As an artist I embrace this in my practice, switching from sculpture to pots and adapting making techniques across disciplines, as I see fit. I’m nothing if not versatile.

I am wearing my Jugpack because the object and its materials allow me to utilise its primary function to carry something outdoors. It is a portable, wearable object, rather than a static sculptural object. I could fill it from the milk vending machine at my greengrocers, or pick and carry fruit, or fill it full of flowers and who knows what else. This isn't Heidi coming down from the Hinterland; this is hi-tech wear with mountaineering roots that belong. Fashion-forward, a new tradition created: 'Anyware' - everyday pottery with anarchic, counter-cultural vibes. I dig it.

Permissions and Influences

The familiarity of the materials helps connect people to objects. I am interested in this and the intersection of craft, quality and hi-performance materials. The artworks selected for my website are relatable, recognisable and familiar: be it from the materials used, to work being placed in the public realm, or pots that fit in the home.

Influences outside of fine art and ceramics complement my varied practice. I am currently researching a combination of post-war French design as well as high-performance materials and polypropylene strapping for packaging; with a side order of surrealism.

Belgian Surrealist Marcel Mariën (b.1920 Antwerp – 1993) was an artist, poet, essayist, photographer, collagist, and filmmaker, and later a Situationist. Star Dancer (1991) and L'introuvable (1937) are two pieces that showcase his prankster tendencies and promote carefully crafted pieces of sculpture.

I am fascinated by other artists' practices, particularly multi-disciplinary artists who use clay. I am curious to explore where it has taken them. Here are a few of my favourites:

Charles Simonds (b. New York, US 1945)

I am interested in how Simonds uses his body, land, action, ritual and explores the sourcing of his materials.

Birth (1970), film 1:39min and Dwellings 1972 (9:43min)

Unglazed clay mini settlements, planted in neglected urban neighbourhoods and shown in art venues.

Colin Self (b. Rackheath, Norfolk 1941)

I like how Self captures nature and humanness in clay, particularly through pieces such as Bowl on Clay and Bowl on Fist (2009), and how he worked collaboratively with potter Mathies Schwarze.

Lidia Zavadsky (b. Drohobych, Ukraine, 1937 – 2001)

Impressive bright, bold, large scale pots – Zavadsky is interested in reconstruction and restoration. She had a show called 'Primarily Jars' and the title alone makes me want to find out more about her work.

Following the writing of these blog posts and drawing together various ideas and influences, I have a sense of a forward direction of travel both in my blog and my creative practice. I feel more informed about my approach towards a new body of work that explores, for example, how I feel about open versus closed vessels. Imagine the action of pouring out the contents of Jugpack, that action versus the function of a completely sealed pot, or one that has a lid. Imagine reading a blog exploring the precarious, evolving expression of ideas; imagine viewing a finely crafted and resolved artwork. Imagine an artwork that decays; imagine an artwork that is preserved. Imagine…

Image credits

Image 1:

Essex Soap Powder, Kirsten Reynolds – @reynolds_art, www.kirstenreynolds.co.uk

Fuzzy Felts! I’d forgotten all about these. I LOVED these! – Nostalgia by J Farrell

Striker Bike – Tintin's photo board by Will Lamb

Silly Putty

Quavers

Tony Hart Gallery

Ford place

Clay pit (1)

Clay pit (2)

Image 2:

Thrown Lidded Pot, Lisa Scantlebury 1993. Stoneware – Photo Andrea Redfern

Image 3:

Meoto Yunomi, Lisa Scantlebury. Thrown Stoneware – Photo Lisa Scantlebury

Image 4:

Shelf Life by Lisa Scantlebury. Thrown Earthenware – Photo Lisa Scantlebury

Images 5-11:

The making of Jugpack – Photos Lisa Scantlebury

Image 12:

Half a cup of tea mug (still Image), Just Half a Cup Please..., Grand Illusions

Image 13:

Trompe-l’oeil Ceramic Sculpture, Marilyn Levine

Image 14:

Slipcast, Lisa Scantlebury 1993. Ceramic, metal – Photo Lisa Scantlebury

Images 15 & 16:

Jugpack, Lisa Scantlebury 2018. Earthenware ceramic, strap – Photo Lisa Scantlebury

Image 17:

L'introuvable, Marcel Marien 1937

Image 18:

Park Model-Fantasy, 1974/1976, ML 01286, Charles Simmonds Museum Ludwig Cologne – Photo JM

Image 19:

1) Bowl on Clay; 2) Bowl on Fist, Colin Self 2009

Image 20:

Lydia Zevetsky, from the exhibition 'Lid Kad', Benyamini Contemporary Ceramics Centre, Tel Aviv, Israel – Photo Shai Ben Ephraim